Ayre Acoustics QB-9 USB SACD Decoding DAC

R24,000.00

These days, it seems you can’t shake a stick without hitting a USB DAC, but Ayre’s QB-9 ($2500) is something a little different. Ayre’s marketing manager, Steve Silberman, was adamant: “The QB-9 isn’t a computer peripheral. It makes computers real high-end music sources.”

The rules have changed today

What makes the QB-9 different? I’ll just hit the high points here. (For the full particulars, see Ayre’s white paper.)

To achieve the maximum resolution, a D/A converter must use a high-precision clock circuit running at a fixed frequency to control the timing of the conversion of each digital sample to an analog voltage. By contrast, almost all USB DACs operate in what’s called adaptive USB mode, which means having to use a variable-frequency clock rather than a fixed-frequency master clock. For various reasons, a computer cannot maintain perfect timing of the data packets it sends a DAC via USB. Most adaptive USB DACs are based on one of Burr-Brown’s PCM270x family of chips. The BB chip typically changes the master-clock frequency to match the average sampling frequency of the data it receives—hence the “adaptive.” The drawback to this, says Ayre (and which John Atkinson’s measurements of other USB DACs seem to confirm), is that adaptive USB DACs tend to have high levels of jitter. Also, the BB receiver chip maxes out at a resolution of 16 bits and a 48kHz sample rate.

The USB standards documents also list a mode of operation called “asynchronous.” This is not to be confused with Asynchronous Sample Rate Converters; asynchronous USB operation is called that because the DAC’s master clock isn’t synchronized to any clocks within the computer. Instead, the DAC is controlled by a high-precision fixed-frequency clock, and, to match this clock, the DAC controls the flow of data packets from the computer to a buffer upstream of the D/A converter chips. The BB 270x chips can be run only in adaptive mode, but Texas Instruments’ TAS1020B USB interface chip, which incorporates an onboard microcontroller and a memory buffer, can operate in asynchronous mode, and will also accommodate sample rates up to 96kHz and word lengths of 24 bits.

For the QB-9, Ayre has licensed the asynchronous technology developed by Wavelength’s Gordon Rankin for the TAS1020B chip. In his life B.A. (Before Audio), Rankin was chief engineer at what he coyly refers to as “the sixth largest manufacturer of PCs in the world.” He spent nearly two years developing the software for the microcontroller that allows the TAS1020B to work in “asynchronous” mode with both PCs and Macs, using only the native drivers included in their operating systems. Rankin’s software for the TI chip is marketed as Streamlength; Ayre is the first company to license it.

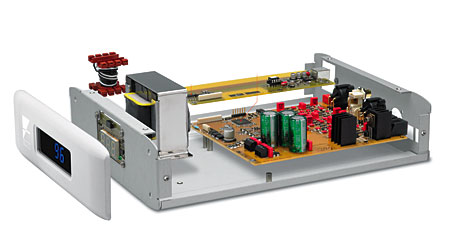

The QB-9 marries Streamlength to the Ayre ethos of zero feedback and fully balanced operation, not to mention Ayre’s new minimum-phase digital reconstruction filter, implemented in a Field-Programmable Gate Array (see my Follow-Up on the Ayre C-5xeMP, July 2009, p.98). Ayre also isolates the USB receiver section from the rest of the audio circuitry with opto-isolators, to prevent any noise generated by the source computer and its host of clocks from polluting the audio signal.

Basically, the QB-9 has a single input—USB, duh—and analog outputs: one set each, balanced and single-ended. A small set of switches on the rear panel offer a choice of four operating configurations. The first is Ayre’s usual Measure/Listen digital filter option (I tend to prefer Listen). The second is Power Mode, which lets you choose between the QB-9 powering on when it detects the computer powering on, or powering up only when it detects incoming data. Another switch lets you turn off the front panel’s display. The fourth switch has no function as yet, but is there in case Ayre thinks up something else for the QB-9 to do.

My soul has been psychedelicized

Setting up the QB-9 in my main system wasn’t as plug’n’play as I’d envisioned. Details mattered—maxing out the RAM on my G4 iBook made a huge difference to the sound, as did matching the sample rates on the computer and DAC. I’d hoped the QB-9 would sort through my 44.1, 48, 88.2, and 96kHz music files and just play each at its native sample rate. Well, it did—but my iBook wasn’t so versatile. I could change the sample rate in the latter’s Audio MIDI setup, but it wouldn’t “take” unless I closed and reopened iTunes. Also, iTunes doesn’t support FLAC, so I had to convert FLAC files to AIF with a bit of freeware called Max.

Technically speaking, none of these are the QB-9’s “shortcomings”; they’re native to the current state of iTunes. Windows-optimized music streaming programs are apparently more forgiving. Ayre offers on its website pages dedicated to tweaking different operating systems from Apple and Microsoft.

I recommend using a separate power conditioner for all the computer bits’n’bobs—in my case, the laptop and a FireWire-connected external hard drive. You probably don’t have to go nuts with the peripheral conditioner; you just want a few degrees of separation from the audio components.

I might get burned up by the sun

The obvious question, I reckon, is that if using a computer as a source component for music isn’t brain-dead easy, why bother? Well, spinning LPs isn’t brain-dead easy either—people put up with the aggravation because they like the sound. Now, for the first time ever, audiophiles can own recordings in their native resolutions, and the places where we can download music in resolutions and sample rates higher than the Compact Disc’s “Red Book” standard are proliferating. I want those higher resolutions, and I want ’em now.

I’ve downloaded files from Linn, Naim, and HDtracks that sound better than any CD I own—and Gordon Rankin, God love ‘im, sent me an external Western Digital Passport 320GB hard drive packed with hi-rez offerings to use for this review. John Atkinson had added the 24-bit, 88.2kHz master files for his recent Cantus, Robert Silverman, and Attention Screen recordings, but also on the drive was a 24-bit/44.1kHz version of Rhapsody, John Atkinson’s recording of pianist Hyperion Knight playing the music of Gershwin (CD, Stereophile STPH010-2)—a significant recording in my digital education. JA had recorded those 1997 sessions at 24 bits, but the CD master, of course, had to be dithered down to 16 bits. Now, hearing those recordings at their 24-bit resolution through the Ayre QB-9 was wonderful. The difference made by those extra eight bits wasn’t tonal or timbral—what had changed was the presence of the music: 24 bits put me there—16 bits simply didn’t.

Also on Rankin’s hard drive was a 24/96 version of the title track of Olu Dara’s Neighborhoods (CD, Atlantic 83391-2). It sets up a lazy groove that just ambles along, and through the QB-9 it popped with life—the congas had more snap, and the shimmering overtones of Dara’s guitar lingered longer in the air. Most of all, that slow groove was more solid—analog lovers like to extol the “flow” of their preferred format, and hi-rez digital seems to do much the same thing. I’ve listened to the CD of Neighborhoods many times since its release in 2001, so I wasn’t reacting to the novelty of the music; instead, I was marveling at how good this old friend sounded at 24/96.

Rankin also included 24/96 files of John Gorka’s The Gypsy Life (DVD-Audio, AIX 83053). I’m a big fan of AIX’s hi-rez releases, and of Gorka, so I cued “I Saw a Stranger with Your Hair.” Wowsers. Lots of big room acoustic and big, big bass sound from Michael Manring, but what floored me was the realism of Gorka’s voice, especially his harmonies with Susan Werner and Amelia Spicer. Those people were in my room—and my room had gotten so big!

Then I discovered that Rankin’s magic box also included David Crosby’s If I Could Only Remember My Name… (Atlantic SD-7203) as 24/96 files. I had to hear “Cowboy Movie.” Holy cow—even when downsampled to 96kGHz by iTunes’ QuickTime engine, it had never sounded like that, not even with pharmaceutical enhancements. The sound was huge, and the crackling guitar exchanges between Crosby, Jerry Garcia, and Jorma Kaukonen were practically physical in their impact. And at the end, when everything just grinds to a halt, I could hear a few seconds of studio ambience to an extent I’d never before experienced.

Producer’s Cut (DVD-A, Rhino 78174) comprises 24/96 files of 14 of Emmylou Harris’s finest recordings. I’ve been listening to that woman since before she met Gram Parsons—I can’t tell you how many times I sat in the Prism coffee house in Charlottesville, Virginia, listening to her within touching distance—so I’ve got a pretty good handle on what her voice sounds like. Producer’s Cut completely nails it—I have never heard “Boulder to Birmingham” sound better. Harris’s voice had a truly physical body supporting it, and her silvery topmost register was burnished even brighter than usual. And, oh yes, in 24/96 I had a deeper emotional connection to her music than ever, if such a thing is possible.

Good work, QB-9.

One thing I’ve almost overlooked is how well the QB-9 performed with non–hi-rez files. Aguston Barrios Mangoré’s “Cueca,” from guitarist David Russell’s The Music of Barrios (CD, Telarc CD-80373), which I’d ripped to my own hard drive as an AIF file, sounded great! Again, I noted an admirable amount of acoustic support for the guitar’s tone, especially when Russell rapped on his soundboard while playing a countermelody high on the frets—ha! made me jump! The absence of artificial texture, and my ability to hear deep into the soundstage, made me suspect that the QB-9 indeed does have low levels of noise and jitter.

They say we don’t listen anyway

I had on hand the Bel Canto’s USB Link 24/96 USB-to-S/PDIF converter ($495) and e.One DAC3 ($2495). The combination, with the USB Link feeding one of the DAC3’s S/PDIF inputs, seemed like a natural for comparison with the Ayre QB-9. I understand that Bel Canto has incorporated some improvements in the e.One DAC3, and I’d been scheduled to send in my sample for those upgrades—but I held off, thinking the Ayre deserved a challenge like the Bel Cantos, which had been making me very, very happy.

Like the Ayre, the USB Link 24/96 will handle high-resolution files and uses the Texas Instruments TAS1020B chip. However, it operates the USB interface in adaptive mode using code developed by Centrance. John Atkinson’s review in May (p.97) indicated a fairly high amount of jitter on the USB Link’s S/PDIF output, but this will be minimized by the DAC3’s data receiver circuit.

Playing the 24-bit/44.1kHz version of Rhapsody, I was hard-pressed to hear a great amount of difference between the QB-9 and the Bel Canto combination. Perhaps the Ayre let me hear deeper into the acoustic of the First United Methodist Church of Albuquerque, but the differences were slight.

On Olu Dara’s “Neighborhoods,” I did feel the Ayre captured the pace slightly better—and perhaps had a tad more depth and roundness in the bass. Slight advantage, Ayre.

On Gorka’s “I Saw a Stranger with Your Hair,” both DACs impressed me with their natural sound and true timbre. I went back and forth several times, noting very minor differences, but nothing that I felt was conclusive. Neither component had a “sound”—as should always be the case in audio but very seldom is.

I did feel the Ayre got that crackle of bottled lightning in Crosby’s “Cowboy Movie” exactly right. The e.One DAC3 with USB Link 24/96 lacked a slight amount of bite—and the QB-9 showed me more of the studio in the fade-out.

On “Boulder to Birmingham,” Emmylou Harris had a bit more sparkle through the Ayre, but only just. Both were digital sound I could live with happily.

And Barrios’ “Cueca”? Again, I preferred the QB-9 for the impact of those soundboard raps. They were phenomenally vivid and startled me every time, even though I know this recording well.

With either the QB-9 or the Bel Canto USB Link 24/96 and e.one DAC3, a computer could indeed be a high-end music source. That’s good news.

The time has come today

At $2500, the Ayre QB-9 isn’t perzackly cheap, but it doesn’t seem as if Ayre has gotten greedy. In fact, I’d wager the company’s profit margin on the QB-9 is tighter than usual. It’s well built and seems to live up to its performance claims. JA’s jitter tests will tell us if it does have the lowest jitter of the USB DACs we’ve tested to date, but my listening impression is that if it’s not the lowest, it’s pretty darn close.

And while computer audio isn’t as boneheaded simple as we’d like it to be, the QB-9 doesn’t add to the complexity. In one respect, it made computer life easier in that it could play all of my hi-rez digital files—and it ignited a mighty lust in me to obtain more. I do not want to go back to 16-bit/44.1kHz CDs. I want long words and high bit rates!

It is a given in the High End that components approach their highest possible peak of performance after they’ve been made obsolete. Perhaps, this one time, we can get it right early in the game. Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so?

I’m sure the QB-9 isn’t Ayre Acoustics’ or Gordon Rankin’s last thought on getting digits out of computers, but they’ve set themselves a pretty darn high bar for the future. I can hardly wait.

Ayre QB-9 DSD

Ayre is one of those companies that quietly gets on with producing innovative, well thought out and in my experience great sounding hardware. I have tried amplifiers and CD players in the past and always mourned their loss when the review period came to an end, so when the opportunity arose to listen to the only digital to analogue converter in the line I was very keen indeed.

The QB-9 DSD is not brand new but late last year it gained the ability to convert DSD, only DSD64 the base sample rate, but this made it rather more of the moment than its strictly PCM processing predecessor. It is a surprisingly single minded converter inasmuch as it only has USB input, thus is dedicated to computer audio sources and the like. The benefits of avoiding switches in the signal path are well known and this presumably is why Ayre chose not to include legacy S/PDIF inputs such as Toslink and coax. Not including AES/EBU however might limit its high end appeal now that streaming bridges are being made with this particular output.

Ayre was an early adopter of asynchronous USB and clearly sees it as the future of digital transfer in audio systems, they have a point. At present USB is the most popular method for sending high resolution audio to a DAC because very few sources for such material have any other output, essentially we are talking about computers or audio components with computers onboard. Asynchronous USB is where the timing of the incoming bitstream is controlled by the USB receiver and not the computer sending the signal. As ever with audio matters there are different ways to achieve asynchronous transfer and just having the technology in the box does not mean you get the best results, the job has to be done properly. In this case it means carefully designed power supplies for the receiver and good filtering to keep the noise that the computer sends along with the signal at bay. Ayre’s experience in designing amplifiers gives them an instant advantage in this respect. This DAC, in keeping with most Ayre compononents, is fully balanced and has a zero feedback output stage, which should mean that in a system with fully balanced amplifiers it will sound better via its balanced outputs, but my preamp is single ended only so that’s how it was auditioned.

The QB-9DSD is an attractive and compact converter with no front panel controls, in fact there are almost no switches at all because you only have the one input and there is no on/off switch. It remains on as long as there is a power lead connected to its mains inlet (see below for the full story). As with the single input this gives it all the markings of a highly purist component, rather more so than is usual for an established high end company. The CAD 1543 DAC takes this approach one stage further by having a captive mains lead but that is an extreme example.

The display on the QB-9 DSD shows the sample rate of the incoming signal, or 64 if it’s DSD, when it’s active or a red dot when it’s not. On the back panel there are the USB input, balanced and single ended outputs, Ayrelink bus connections and a row of dip switches. These offer listen/measure digital filter options, two power modes depending on how the DAC is used, it can turn on only when there is a signal if required, and a display on/off including dimming in an Ayre system. There is also a swtich for class 1 or 2 audio over USB, class 1 offering maximum compatibility but is limited to 96kHz, class 2 is therefore the option to pick if you have dedicated audio software on the PC that can output sample rates above 96kHz.

Air for Ayre

When the Ayre arrived chez Kennedy I used it with a Macbook Air laptop running Audirvana Plus sofware, and this produced a pretty decent result albeit one that limited ultimate performance. The QB-9DSD is an immensely transparent and relaxed converter and it while it makes it obvious that a general purpose laptop is not the be all and end all it also rewards upgrades at the beginning of the chain with significant improvements in sound quality. This much became obvious when I started to use it with a Melco N1A digital music store, an audio grade NAS with USB output as well as Ethernet.

But my initial impressions were gained with the Mac and they were pretty positive. Beethoven’s Symphony No.7, specifically the Allegretto (Barenboim, Beethoven For All Symphony, 24/96, Decca), offered up masses of low level detail that revealed the nature of the recording venue’s acoustic and the textures of the instruments, the bowed basses being particularly glorious. The sense of restrained power is particularly intoxicating with this piece and the Ayre delivered it with complete clarity. The piece always sounds powerful but now it did this while offering up the multiplicity of different instruments and all their subtle timbres. It was so good that I felt inclined to listen to the whole symphony.

With a DSD version of Dylan’s ‘Visions of Johanna’ (Blonde On Blonde, CBS) the ‘harp’ jumps out of the soundstage and the bass line is easy to follow, as is the wiry guitar. It was also surprising how well this almost lo-fi track images. When the Melco arrived however, things moved into another gear, now the fine detail was coming from deeper in the mix and this produced expansive sonic vistas reaching back and out from the speakers in thrilling fashion. Recording allowing of course, not everything is recorded to give great scale but La Folia (Atrium Musicae De Madrid, Gregorio Paniagua, Harmonia Mundi) was. Originally an analogue recording but released on SACD some time ago this is a spectacular piece of work when played through a DAC of this calibre. The reverb is immaculately reproduced and the ancient instruments have a strong presence in the room thanks to the substantial and clear acoustic character captured by the recording. Nils Lofgren’s ‘Keith Don’t Go’ is a bit different (Acoustic Live, Demon), clearly a polished production it presents his crisp steel strings with all the lush tonal richness of the wooden acoustic guitar, again presence is first rate.

The Ayre is unusually relaxed and effortless, its character is so minimal that it could be too restrained for some tastes. Its sound comes closer to the aforementioned CAD 1543 than almost anything I have heard, and that is an impressive achievement given that the CAD costs more than twice as much. There must be something in the lack of switches, by comparison most DACs have an edge to them, this gives more attack to leading edges but is really a subtle form of distortion, a barrier between you and the music. The Ayre has so little in the way of discernible character that you get a lot more colour and subtlety from the music, you can hear what’s going on in complex pieces more easily and appreciate nuances in the way that musicians sing and play, and for that matter the way that engineers have recorded them.

The pace, rhythm and timing enthusiast might feel that the Ayre does not sound fast but that’s because it’s devoid of the emphasis on leading edges that many ‘fast’ sounding components have. I suspect that with the right source you could get a pacey, taught sound out of this DAC but that would be a waste of its transparency, what it deserves is a source with minimal character as well, that way it will be able to tell you the most about the original sound.

When I first started to listen to the QB-9DSD I was a little underwhelmed, that was largely because my laptop is not a good enough source for such a revealing converter. Since using it with the Melco my opinion has swung 180 degrees and I think this is one of the most transparent and realistic sounding DACs available. It makes instruments and voices sound more real than other very good converters and has as natural a sound as the best turntables. Timing is not in quite that league but that again I suspect is a source issue, at the price the Ayre is a revelation.

Type: USB DAC

Converter: ESS Sabre Ultra 9016S 32-bit

Input: Asynchronous USB

Formats: PCM 44.1 kHz, 48 kHz, 88.2 kHz, 96 kHz, 176.4 kHz, 192 kHz (up to 24 bits), DSD64

Signal/Noise: 110 dB (unweighted)

Outputs: Balanced XLR, single ended RCA phono

Output Level : 4 volts balanced, 2 volts single-ended

Minimum phase digital filter

Dimensions WxDxH: 21.5cm x 29cm x 7.5cm (8.5″ x 11.5″ x 3″)

Weight : 2.3kg (5 pounds)

Description

- Asynchronous transfer mode for USB input.

- DSD or PCM input over USB.

- Minimum phase digital filter.

- Single-pass 16x oversampling.

- zero-feedback, fully-balanced discrete circuitry.

- Equilock circuitry for active gain devices.

- Ayre Conditioner power-line RFI filter.

- AyreLink communication system.

Frequency Response

DC – 20 kHz (44.1 kHz sample rate)

DC – 22 kHz (48 kHz sample rate)

DC – 40 kHz (88.2 kHz sample rate)

DC – 44 kHz (96 kHz sample rate)

DC – 80 kHz (176.4 kHz sample rate)

DC – 88 kHz (192 kHz sample rate)

DC – 80 kHz (2.8224 MHz sample rate – DoP )

Signal/Noise

110 dB (unweighted)

Output Level

4 volts balanced, 2 volts single-ended

Input

1 USB

PCM 44.1 kHz, 48 kHz, 88.2 kHz, 96 kHz, 176.4 kHz, 192 kHz (up to 24 bits), DSD64

Dimensions

8.5″W x 11.5″D x 3″H (21.5cm x 29cm x 7.5cm)

Weight

5 pounds (2.3 kg)