PSB Synchrony One Speakers

R32,000.00

When PSB’s Paul Barton releases a new speaker, I take note of it. The very first speakers I bought over 25 years ago were PSB Avanté IIs, which I used for about seven years. So paying attention to PSB speakers is kind of a nostalgia thing for me, but it’s also a professional matter. Barton has attained near-legendary status as a speaker designer who knows how to marry the art of loudspeaker design with hard science. Probably because of that, he has over the years created many speakers that have become benchmarks for combining high performance and good value.

Therefore, when PSB offered the new Synchrony speakers for review, I was glad to take on the assignments myself. Initially, I reviewed the bookshelf-sized Two B in April on SoundStage! A/V, and now I’m reviewing the Synchrony One here on SoundStage! The Two B is the entry-level model in the series and sells for $1500 USD per pair, whereas the One is at the top of the line and sells for $4500 per pair.

Description

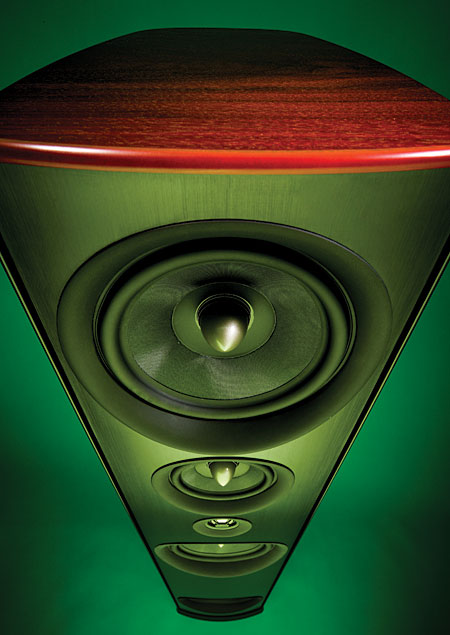

At first glance, the Synchrony One might seem like an ordinary floorstanding design. It measures 43″H x 9″W x 13″D, weighs 60 pounds, and appears conspicuously simple, particularly with the grille on. However, a closer inspection reveals there is some impressive engineering going on with this not-so-conventional five-driver, three-way design.

The front baffle and back panel are aluminum, as is the speaker’s base. What’s more, the front baffle is constructed with two aluminum layers, which allows for the drivers to be mounted to the back layer with a rubber molding surrounding the drivers and extending to the front layer. This is done to give the drivers a rock-solid footing on the very solid baffle but with minimal energy transferred to the front-most portion of the baffle to keep resonances down. Cosmetically, that rubber molding also covers up the drivers’ unsightly bolts.

The curved side panels are made from seven-ply MDF that’s finished with a real-wood veneer. The top is also MDF, but it’s flat. Barton described to me how the curved panels are made. First, the thin layers are bent and glue is placed between. Then, when all layers are together, the whole thing is essentially “microwaved” to make it set. After that, it’s solid.

What’s more interesting is how the side panels are affixed to the front and rear aluminum panels with a clever slotting technique that I haven’t seen used in any other speaker. It’s difficult to describe with words, but suffice it to say that the curved wood side panels slide into the aluminum’s grooves. The result is an incredibly sturdy speaker structure with no visible screws or bolts on any side.

The finish options are cherry or black-ash real-wood veneer. Looks-wise, the cherry wins hands down — at least in my opinion. Black ash will be preferred by people who want their speakers to look less conspicuous.

I have much admiration for the visual attributes and the clever construction methods of the Synchrony One, but I can’t overlook what’s going on inside the box. Take the way the three 6 1/2″ woofers work, for example. They’re all identical fiberglass-based cone designs placed at the top, midpoint, and bottom of the front baffle and spec’d by PSB to deliver flat bass into the 30Hz range, with a -10dB point of 24Hz. For such a modest-sized cabinet, that’s impressively deep bass.

Each woofer is spaced from the others and has its own compartment within the cabinet. So, if you crack the One apart, you’ll see separate sections for each woofer along with a port out the back for each. This is an important design element because, with a tall and narrow cabinet like the One’s, if the cabinet were left wide open inside, nasty standing waves corresponding to the length of the cabinet would develop internally. Dividing the cabinet into compartments helps to eliminate that.

Why space out the woofers? The main reason Barton has done this is to combat what’s known as the floor-bounce effect. This is an early-reflection thing that happens when the direct signal from a driver is interfered with by the indirect signal that travels off-axis from the same driver to a nearby surface — the first usually being the floor — bounces off it, and then arrives at the listener’s ears just a little later than the initial sound.

Obviously, this reflection happens with walls and ceilings too; however, a designer can attack only so much at once. Therefore, getting rid of that nasty floor reflection — or at least reducing it — is what Barton has attempted to address by spacing the woofers. Because all three drivers are spaced apart, they each vary significantly enough in distance from the listener’s ears that they’ll each have different frequencies affected by the floor bounce. Therefore, Barton has altered the response of each woofer so that at each of their main floor-bounce frequencies, the output in that region is attenuated significantly to minimize the interference. As a result, all three woofers have quite different frequency-response characteristics when you look at them independently. Furthermore, because they’ve been attenuated in their floor-bounce range, they’re not “flat” (i.e., they don’t display equal amplitude across their operating range). Now the really nifty part: Barton says that even though each woofer’s response isn’t the same or flat, the summed response of all three working together is flat. So the speaker is still “neutral.”

In comparison, the midrange and tweeter operate far more conventionally. The 4″ midrange driver, which transitions in at about 500Hz, also has a fiberglass cone and a rubber surround. The midrange driver hands off to the 1″ titanium-dome tweeter at about 2.2kHz. Fourth-order slopes are used throughout to minimize driver overlap, and the crossover points were chosen to ensure proper dispersion characteristics between the drivers for smooth on- and off-axis response.

One more thing to take note of is the fact that the tweeter is mounted below the midrange driver and the top woofer. This has become a hallmark of Barton’s pricier speakers and is contrary to the way it’s done with most speakers, whether two- or three-way, which would normally have the tweeter at the top. Barton likes this flip-flopped arrangement because he says it allows him to control the summing of the drivers more easily, so no cancellations happen at the listening axis or above (seated or standing height). Instead, cancellations — which occur with all multi-way speakers because the different drive units are all in differing spaces — are directed toward the floor.

Large, well-made binding posts are inset on the backside near the floor. There are two sets, so you can single- or biwire the Synchrony Ones. I kept it simple and single-wired.

Finally, a few of the PSB-supplied specs. Frequency response is rated +/-1.5dB from 30Hz-23kHz, anechoic sensitivity is rated at 88dB/W/m, and impedance is said to hover around 4 ohms.

Sound

The Synchrony One can go much lower in the bass than the Two B — no surprise, given the increased size of the One and the fact that it has three 6 1/2″ bass drivers versus the Two B’s single 5 1/4″ woofer — but, on top of that, it reaches much deeper, with authority and control, than many speakers its own size. This may be the largest Synchrony speaker, but it’s not nearly as big as some speakers that have come into my room, yet it has deeper bass. When I played the opening tracks from the Cowboy Junkies’ The Trinity Session CD [RCA 8568-2-R], I got those deep, room-pressurizing thumps that the Two B could only hint at, most speakers whimper with, and some completely miss.

Furthermore, the bass wasn’t just deep, but well controlled, super tight, and without any boost or emphasis in the upper-bass region (100-150Hz or so) that gives the illusion of really deep bass when it’s not there. The One delivers the real thing — nothing I heard in my room would cause me to dispute the 30Hz specification. So when it came to a drummer going full throttle, as Abraham Laboriel, Jr. does on “Objection (Tango),” the opening track on Shakira’s Laundry Service CD [Sony 63900], it sounds like a full-scale drum kit through the Ones. For such a modestly sized, moderately priced design, the Synchrony One delivers outstanding bass performance.

The One’s ability to play loud is just as notable, bettering all like-sized speakers that I’ve reviewed to date. The kind of dynamic swings the Ones are capable of are awe-inspiring and sure to make the speaker a hit with those who like to re-create sound at close-to-lifelike levels, something fans of rock and large-scale orchestral works should take note.

For example, I’m a big fan of Martin Scorsese’s Shine a Light “rockumentary,” which features the Rolling Stones live at New York’s Beacon Theatre in 2006. This film was released to theaters in early 2008 and is just about to be released on Blu-ray and DVD. There are also two soundtrack versions available on CD. I first saw Shine a Light at an IMAX theater and I rushed out the next day to buy the two-disc, deluxe CD [Universal B001096102] that contains all the film’s songs and a little bit more.

The CD opens up with an explosive version of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” that has Keith Richard’s guitar leading the charge with Mick Jagger’s voice quickly following him in. The track deserves (needs!) to be played ultra loud to give that live-in-the-theater feeling, which the One handled with aplomb. But playing loud isn’t enough — a speaker has to stay clean doing so. The Synchrony One can go from whisper quiet to stadium-concert loud in an instant and remain composed the entire time. The One is clean-sounding at everything from the lowest to the highest listening levels, and this is remarkable, given the speaker’s modest size.

But there’s a catch: To play the Synchrony Ones super loud, you need an amplifier that can deliver current. The One has decent sensitivity, but its impedance is low and likely to cause some amplifiers grief if they can’t handle a tough load. I suspect it has mostly to do with the three woofers working together amidst the rather complex crossover configuration. I used the One with Stello M200 mono amps and a Simaudio Moon Evolution W-7 stereo amp and there was never an issue — these amplifiers can deliver about 150 watts into 8 ohms, and they take on tough speaker loads without flinching. However, when I hooked up the much smaller Simaudio Moon i-1 integrated amp that’s rated at just 50Wpc into 8 ohms, it held together well enough at a normal listening level, but it clipped severely when I went past that. Quite simply, if you want to play these speakers at the levels I described and not risk damage to the speakers or the amp, I recommend a suitably powerful amplifier that stays stable into low impedances — definitely as low as 4 ohms, ideally down to 2.

The One’s ability to play deep and loud was impressive, but, frankly, I expected this going in. However, something I didn’t expect from the Synchrony One impressed me far more: the level of midrange clarity, detail, and tonal accuracy. When it comes to these traits, the One is not only a clear step up from the Two B but from any other speaker near its price, and some above.

For instance, Johnny Cash’s American Recordings CDs sound incredibly rich and robust, but on many speakers they can end up sounding too full — to the point where Cash’s voice is obscured, particularly at high volume. I was astonished to hear how clear and detailed the Synchrony One played these recordings, carving the musicians out of space like no other speaker I’ve heard. The clarity was uncanny, so much so that I pulled out recording after recording to find out what I could hear from them, and I sat astonished each time. In fact, the Synchrony One reminded me of an electrostatic speaker for offering the kind of transparency it has in the midrange.

This extraordinary level of detail and clarity contributed to a soundstage with a high degree of placement precision and an impressive re-creation of space. Coupled with the deep bass that’s not only heard but felt, the Synchrony One makes it a snap to hear every detail in the recording and to imagine the listeners in their recorded space. In fact, I couldn’t help but think that the Ones would make fabulous recording monitors because of their deep, controlled bass, extraordinary neutrality, exceptional retrieval of musical detail, and ability to play music at lifelike levels.

On the other hand, where the Synchrony One doesn’t break any new ground is in an area I haven’t touched on yet — the high, high highs. The One uses the same tweeter as the Two B, as well as every other speaker in the Synchrony line. That’s not necessarily a bad thing — the One and Two B sound commendably clean up to the stratosphere. But it’s just not the ultra-special performance that they have in the bass and the mids, particularly when you’ve heard some of the new tweeters from other companies — notably Paradigm’s new beryllium tweeter that shows up in the new Signature line. I reviewed the S1 v.2 late last year, and I found it to have the most effortless and accurate ultra-high-frequency performance that I’ve heard to date, bettering that of speakers I’ve heard that use the Scan-Speak Revelator tweeter, my previous favorite because it sounds so sweet. The Two B and One are very good up top, but I’ve heard some speakers sound better.

But this doesn’t take away from what the One achieves, which would be a lot for a speaker twice the size and price. Instead, you get some cost-no-object sonic touches at a mid-level price.

Comparison

The Synchrony One reminds me of Mirage’s OM Design OMD-28, which retails for $7500 per pair. It’s not that they’re sonically similar — as you’ll see, there are some quite substantial differences — but that they both offer innovative technology, outstanding build quality, and cost-no-object fidelity at what can be considered reasonable asking prices.

First, the big difference: The OMD-28 is a 360-degree-radiating speaker, but it directs more energy to the front than a standard omnidirectional speaker, which makes its presentation a little bit more like that of a front radiator. However, there’s no denying that the omnidirectional elements of the design allow it to project an enormous soundstage with extraordinary width that goes beyond the speakers’ edges and depth that reaches past the front wall of the room. Its sound is enveloping and, any which way you cut it, quite awesome to hear. However, the ‘28s’ expansive soundstage is offset by imaging precision that’s so-so when you compare it to a speaker like the Synchrony One. A pair of Ones doesn’t make as big a soundstage, but they do create one that’s more precise. It’s no problem to pinpoint where the performers are with the Ones, whereas with the OMD-28s placement is not as specific.

Another big difference is in the bass. Both reach extremely low, but the OMD-28 is the winner. Mirage rates the OMD-28’s -10dB point at 18Hz, something I believe because the speakers sound strong down there. However, the biggest difference in the bass isn’t the depth but rather the weight. The OMD-28s sound much weightier and have more heft, which has something to do with how low they go and also with some upper-bass emphasis that the Synchrony Ones don’t have. None of this is a knock against the Synchrony Ones. The OMD-28s are true full-range speakers at a commensurate asking price; the Ones, on the other hand, offer nearly full-range performance that’s more than impressive at their price. Most people don’t get 30Hz from their speakers, even very large speakers, and the Synchrony Ones certainly achieve that.

Then, of course, there are similarities starting with the fact that both speakers need a strong, current-capable amplifier to be at their best and to play loud. Both will clip an underpowered amplifier and, in my opinion, wouldn’t be well-suited for tubes. Beefy solid-state is the order of the day for the Synchrony Ones or the OMD-28s.

They also both sound extremely well balanced from the lower mids on up, although in absolute terms, I suspect the Ones are the more linear of the two. PSB seems to design most of their upper-end speakers to be the pinnacle of neutrality, whereas Mirage goes for a more forgiving sound. When you compare the two side by side, the OMD-28s have a slightly more relaxed and velvety sound, whereas the Synchrony Ones sound vivid and precise.

Both speakers are quite similar in the extreme highs. They employ clean-sounding tweeters that are hard to fault until you hear the latest generation of great tweeters, such as that beryllium number from Paradigm. When you compare the OMD-28s and Synchrony Ones to that standard you realize they’re not quite as effortless as the very best.

The OMD-28 is a true full-range design that’s built to an extremely high standard and can compete with speakers multiples of its price. I’ve often said that if any other company tried to build the ’28, it would likely cost two to three times as much, if they could build it at all. That’s why I consider the OMD-28 one of the great bargains in high-end audio today. The same thing can be said about the Synchrony One. It may be more conventional than the OMD-28 — it’s a standard front-radiator and not quite as full-rangey — but it also features advanced technology that outclasses designs multiples of its price. Obviously, if the OMD-28 is a great bargain, the Synchrony One can be considered an even greater one.

Conclusion

PSB’s Paul Barton has been in the loudspeaker game for over 30 years. In that time, you’d think that he might slow down, or at least run out of ideas. Based on what I experienced with the Synchrony One, there’s no fear of that just yet. The One is visually appealing, technically advanced and sonically superb. Overall, it’s really hard to fault. The only concern with the One is to make sure that you partner it with a sturdy amplifier able to deal with a somewhat difficult load or you won’t hear all that it can do. With a proper amp, though, you’ll find that these speakers are capable of remarkable performance from top to bottom with bass performance that is notable for the speakers’ size and price, loudness capabilities that belong to speakers twice the size, and a midrange presentation that sets a new standard for tonal accuracy, clarity and detail.

All in all, the Synchrony One is an impressive statement in the Synchrony line and, when all things are considered, it’s being offered at a price that’s downright low. Barton has found a way to blend styling with performance and, from what I can tell, not compromise either in any significant way. To my ears, the Synchrony One is the best PSB speaker yet, and it establishes a benchmark for value and performance — something that seems synonymous with Paul Barton’s name.

I’ve been listening a lot of late to Smetana’s tone poem Má Vlast, with Sir Colin Davis conducting the London Symphony Orchestra (SACD, LSO Live LSO0516). Recorded in concert in London’s Barbican—one of my least favorite halls—the sound is a little on the dry side. However, from the resonant harp intro of the first movement through each string entry, each instrumental choir was delicately delineated in space, and every instrumental tone color was presented without coloration or undue emphasis. This speaker was also a natural for showing off that masterpiece of orchestration, Benjamin Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. My longtime favorite recording is with the composer conducting the LSO in London’s Kingsway Hall (reissued on CD as Decca 417 509-2 or JVC XRCD 0226-2), but this 1963 recording sounded a bit too brash through the PSBs. A modern recording, of Paavo Järvi conducting the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (SACD, Telarc SACD-60660), sounded very much more natural at high frequencies, and had much the same weight and impact in the bass as the English performance.

The top octaves sounded smooth to me on this Telarc SACD—the delicately brushed triangle at the end of the final variation before the fugue was beautifully resolved, without sounding spotlit—but Erick Lichte was less tolerant than I of the PSB’s performance in this region. However, in the “Measurements” sidebar accompanying this review, I wonder if he was reacting instead to the small response peak between 16 and 18kHz, which, unlike me, he could hear. The height of this peak is not affected by the perforated-metal grille, which proved to be transparent other than suppressing the speaker’s output by a couple of dB between 9 and 16kHz. Even so, at the end of the mixing sessions we listened to one of my 2008 “Records To Die For,” violinist Hilary Hahn performing Vaughan Williams’ song of serenity, A Lark Ascending (SACD, Deutsche Grammophon 28947-48732-6), with nary a complaint from either of us.

The Synchrony One really shone with classical orchestral music, in part because its slightly warm upper bass and extended low bass gave the sound a firm underpinning. The double basses on the Telarc Britten SACD had the optimal combination of attack and weight to their tone. This speaker did go surprisingly low in the bass, considering its relatively small stature. When I listened to the 1/3-octave warble tones on my Editor’s Choice (CD, Stereophile STPH016-2), the Synchrony One gave full measure down to the 25Hz band, with only the 20Hz warble inaudible. The half-step–spaced tonebursts on the same CD were reproduced cleanly and evenly from the lowest frequency, 32Hz, with little sign of doubling in the lowest two octaves and without undue emphasis on any specific note. There was also a commendable lack of wind noise from the flared ports, even at high levels.

Both the dual-mono pink noise and the in-phase bass-guitar tracks on Editor’s Choice were reproduced as they should be: as narrow, central images without any frequencies splashing to the sides. With true stereo recordings, such as the Gershwin Prelude arrangements on Editor’s Choice, there was no sense of images being localized at the speaker positions. Instead, individual instrumental images were precisely and solidly located in the plane between and behind the speakers. And when out-of-phase information was present in the recording, such as some of the effects on Trentemøller’s album of chill-out music, The Last Resort (Pokerflat PFRCD18), these wrapped around to the sides in a stable, nonphasey manner.

Not only was the PSBs’ stereo imaging stable, precise, and accurate, but throughout my auditioning of the Synchrony Ones I kept getting the feeling that I could hear farther into the soundstage that I had been used to. The timpani and the xylophone in the percussion variation of the Cincinnati Britten recording were set unambiguously behind the orchestra’s woodwind and string choirs. This was not because the speakers were suppressing mid-treble energy, a not-uncommon means for a speaker designer to fake the impression of image depth—the PSBs were, if anything, a little hot in this region. Instead, there was such an absence of spuriae that recorded detail was more readily perceived.

But, as I said, this superb retrieval of recorded detail was accompanied by a slight lift in the presence region. This was not nearly so much as to add brightness to the balance, but voices were presented as being more forward in the mix. With the Cantus mixes Erick and I were working on, we felt we had to slightly reduce the level of the closer-sounding cardioid mikes in the mix to compensate for the more distant-sounding omnis. With recordings that are themselves overcooked in the highs—Bruce Springsteen’s dreadful-sounding Seeger Sessions, for example (DualDisc, Columbia 82876 82867-2)—it all became a bit too much in-your-face. But with more sensibly balanced rock recordings, such as So Real, the Jeff Buckley compilation released on the 10th anniversary of the singer’s death (CD, Columbia/Legacy), the PSBs effectively drew forth the music from the mix.

For this reason, the Synchrony One proved a better match to the warmer-sounding Mark Levinson No.380S preamp and No.33H power amps than the cooler Parasound combination of Halo JC 2 and Halo JC 1s, despite the Levinsons fattening up the midbass. Stereophile‘s latest CD, a reissue of Robert Silverman performing the two Rachmaninoff piano sonatas (STPH019-2), now sounded a bit too plummy, even with the bottom ports plugged. I ended up using the Mark Levinson No.380S preamp with the Halo JC 1 amplifiers, which gave the optimal top-to-bottom balance with the PSBs.

As I finish writing this report, I’m listening to the provisional 24-bit/88.2kHz mix Erick and I did of Cantus performing Lux aurumque (Golden Light), Eric Whitacre’s 2001 setting of a poem by Edward Esch translated into Latin by Charles Anthony Silvestri. Whitacre constructs patterns of tone clusters that slowly move stepwise, leaving suspensions that you think will clash yet sound exquisitely tonal. Each of the nine singers was clearly and precisely positioned in space by the PSBs, with the deliciously warm reverberation of the Great Hall of Goshen College reinforcing the effect of the suspended notes in the score. And when, on the music’s final page, the work modulates—finally—to the major, with the basses rocking back and forth between low C-sharps and D-sharps under a long-held high G-sharp from the tenors (who faced away from the mikes for this passage, in order to light up the hall with sound), the superbly neutral midrange and the low-frequency clarity of the Synchrony Ones filled my room with shimmering harmonies. Ah. It’s hard to see how it could get much better.

Summations

The last two speakers I reviewed, the Sonus Faber Cremona Elipsa (December 2007) and the KEF Reference 207/2 (February 2008), each cost around $20,000/pair. As much as I was impressed by those highfliers, PSB’s Synchrony One reached almost as high for just $4500/pair. Its slightly forward low treble will work better with laid-back amplification and sources, and its warmish midbass region will require that care be taken with room placement and system matching. But when everything is optimally set up, the Synchrony One offers surprisingly deep bass for a relatively small speaker; a neutral, uncolored midrange; smooth, grain-free highs; and superbly stable and accurate stereo imaging. It is also superbly finished and looks beautiful. Highly recommended. And when you consider the price, very highly recommended.

Description

Specifications

- Design: 3-Way, Ported

- Drivers: One 1″ Titanium Dome Tweeter, One 4″ Midrange, Three 6.5″ Woofers

- MFR: 33 Hz – 20 kHz, ± 1.5 dB

- Nominal Impedance: 4 Ohms

- Sensitivity: 90 dB/2.83v/m

- Crossover Frequencies: 500 Hz, 2.2 kHz

- Maximum Power: 300 Watts

- Dimensions: 43″ H x 8.75″ W x 12.75″ D

- Weight: 61 Pounds/each

- Finish: Black Ash or Dark Cherry

- MSRP: $5,000/pair USA