Ayre KX-R line preamplifier (Ultra High End)

R145,000.00

I can’t think of a product that was as eagerly anticipated as was Ayre’s KX-R preamplifier ($18,500). Following in the footsteps of Ayre’s MX-R monoblock amplifier, a Stereophile 2007 Product of the Year, and milled, like the MX-R, from a 75-lb billet of aluminum, the KX-R also shares with its monoblock stablemate the Ayre ethos of zero feedback and fully balanced operation. But what really caused the buzz was the declaration by Ayre founder and chief designer Charles Hansen that the KX-R, with its use of a technology he calls Variable Gain Transconductance (VGT) to control the volume, would set new standards for signal/noise ratio.

“The reason nobody ever talks about this issue,” said Hansen, when he previewed the preamplifier to his dealers (and me) just before the CEDIA Expo in September 2007, “is that it’s like the air—it’s omnipresent, so nobody even thinks about its existence. Almost every preamplifier on the market uses an attenuator [ahead of the output stage] to reduce the gain. There are two problems with this: 1) once you get beyond 10k or 20k ohms [series resistance], you begin to affect frequency response along with the volume; and 2) the active circuitry outputs a constant noise voltage—increase the volume level and you increase the signal/noise ratio. The maximum SNR is therefore at full output, which nobody listens at. With VGT, the SNR is constant, regardless of volume setting.”

The KX-R is a seriously gorgeous piece of audio eye candy, so I implored Hansen to let me review it for Stereophile.

“No problem,” he told me, “but we’ve learned from experience. First we need to finalize the design, then we’ll satisfy pre-orders and stock our dealers. After that, we’ll let the press listen.”

Those eight months were long.

Hang time

“Before I talk about the KX-R,” Charles Hansen said to me, “I have to explain that it was designed with what I can only describe as an extreme degree of madness. That’s to say that, in addition to working the kinks out of VGT, we examined everything, even stuff like the panel display.

“Pretty much 99.99% of all front-panel displays are ‘multiplexed,’ which means that not all of the dots are on all the time—they flash, much like the pixels on an old CRT monitor—and turning those dots on and off rapidly creates electrical noise that can radiate into the rest of the circuitry, degrading the sound. We found a special display that is not multiplexed—the segments are always on, and no electrical noise is generated. The catch, of course, is price: We take about a tenfold price hit for that.”

On to VGT. The active device in the KX-R is a FET (a transconductance device), meaning that the input voltage controls the output current. The current needs to be changed back to an output voltage later in the circuit, which in a conventional design is typically accomplished with a fixed resistor. This is called a “transimpedance” device because impedance is the opposite of conductance.

“In the KX-R, the idea is very simple,” Hansen said. “We simply use a variable resistance instead of a fixed resistance. Changing the value of the resistance changes the gain of the circuit. With a variable-gain circuit there is no input attenuator, as is normally found in a preamplifier. This brings about several advantages: The input impedance is not restricted by the value of the volume control (input attenuator). I mentioned that with conventional attenuators, the frequency response can vary with volume. In contrast, the KX-R has an input impedance of 1M ohm per phase, and the frequency response goes out past 250kHz regardless of volume setting. Another benefit is that the signal path is simplified, and there are fewer switches in the way.

“With VGT, the signal/noise ratio is constant regardless of the volume setting. A typical listening level might be 20dB below full gain, which translates into an effective increase in S/N ratio of 20dB. This is on top of an already quiet circuit, and improves the resolution of low-level detail audibly.”

If VGT were simple, Hansen observed, everybody would be doing it. “I’m not saying we invented this. PS Audio’s VCA technology sounds like they might be doing something along these lines, and I suspect CEC might be doing something in the same ballpark. I don’t know, because nobody’s talking about the real intricacies of their designs—and neither am I.”

Key to VGT was Ayre’s development of what they call EquiLock circuitry for the MX-R monoblock. “In a conventional circuit, the gain transistor has a load, usually either a resistor or a current source,” Hansen said. “When the current through the gain transistor changes, then the voltage across the load also changes, which, in turn, means that the voltage across the gain transistor is changing. In fact, all of the parameters (transconductance, capacitance, etc.) vary when the voltage across the transistor varies.

“The EquiLock circuit adds another transistor between the gain transistor and the load. (In our case, the load is actually a current mirror.) This extra transistor holds the voltage of the gain transistor at a fixed level while still transmitting the changes in current to the load (the current mirror). By stabilizing the voltage across the gain transistor, all of the parameters of the gain transistor are also stabilized. The circuit is very similar to a cascode circuit, which has been used by other manufacturers, but EquiLock is an improvement over a conventional cascode circuit.”

And there are elements that make VGT difficult to pull off. The circuit Hansen developed works only with zero-feedback designs, which just happen to be what Ayre specializes in. “It might take a while for others to catch up,” Hansen cackled.

Also, since the signal is not attenuated before entering the active circuitry, source components with extremely high outputs could have been problematic. “We had to do a fair amount of work to ameliorate this potential problem,” Hansen said. “With a typical source of 2V to 4V balanced output, the distortion is around 0.001% to 0.002%. Increasing the input to 8V RMS, as some digital products produce, will bring the distortion up to around 0.008% to 0.01%.”

Hansen chose to set the input impedance at a high 1M ohm per phase (2M ohms balanced). “You know how, when you load a moving-coil cartridge up to 47k [ohms], everything just sounds more open and alive? We believe the same thing is true of any input. We chose 1M ohm per phase because it sounded best to us—I believe that if something’s good, more is better, and that’s the amount that sounded truest to us. On the other hand, if something’s bad, don’t use it—which is our philosophy on feedback.”

The KX-R has the usual Ayre virtues, including Ayre Conditioner powerline RFI filtration. It also has an AyreLink circuit, which allows other AyreLink-equipped gear to be connected via ordinary two-line phone cables. Turning on any AyreLink component turns them all on and, when AyreLink-equipped sources are brought to market, turning on the source will also switch the KX-R to that input. The KX-R also comes equipped with a remote control that, if somewhat large, is convenient for everyday use.

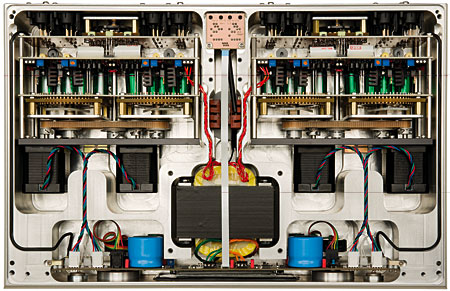

The KX-R doesn’t have an external power supply. Instead, each part of the circuit resides in its own milled compartment: The control section, the audio circuit, and the power supply are therefore isolated from one another by substantial aluminum barriers. Hansen had to have made special transformers to get the KX-R to match the MX-R’s shape; while the models are the same size, the KX-R’s front panel is on what would be a side panel of the monoblock.

Solid air

In my line of work, unpacking and setting up new gear is usually relatively unexciting. The KX-R was different. For one thing, it’s deceptively small for its 40-lb weight, so just unpacking it was an adventure. Then, the rear panel is laid out logically—at least, according to Charles Hansen. In electronic terms, he’s right: the signal paths are short. However, the mirror-image layout on the rear panel of four single-ended inputs, four balanced XLR inputs, two balanced XLR outputs (no SE option), and two balanced XLR tape outputs might confuse ordinary mortals—especially as they’re not labeled but numbered. The owner’s manual suggests you make notes of what you plugged into where.

Those notes will come in handy at the next stage of setup, which is “activating” those inputs. On power-up, if no inputs have been activated, the KX-R automatically enters Setup mode, its display flashing “Set 1 Unused.” On either side of the display is a scroll wheel: the one on the left scrolls through the inputs, the one on the right through a list of names you can apply to the input, ranging from the generic (CD, DVD, Digital) to the specific (all Ayre models). Advanced users can input custom names, if they wish. Other adjustments accessible in Setup mode are of gain offset, channel balance, and bypass (for integration with a surround-sound processor).

Only the inputs that have been named, and thus activated, can receive a signal. When an input is unused, the KX-R removes it from the circuit and lifts its ground (as it does to inputs not currently in use)—which prevents noise from bleeding through to the active input and the rest of the audio circuit.

Once an input has been activated, the two scroll wheels revert to their primary functions: the left one is the source selector, the right controls volume. These wheels are actually optical encoders that send pulses to stepper motors that operate custom-designed, “applied-force” rotary switches with silver contacts. (These motors emit an audible and weighty thump in operation.) The front panel also sports Standby and Mute touch switches.

All of these functions, and many more, are also actuated by the remote control. The KX-R’s volume control has 61 steps of 1dB each—see “Measurements” sidebar—which effectively meant that I got precisely the level I wanted every time—I never had to settle for “almost right.”

At first I paired the KX-R with my Musical Fidelity Nu-Vista 300 power amplifier, which has only single-ended inputs, so I had to use an XLR-to-RCA adapter, which cost me 6dB of gain—not that I noticed any problems owing to that. Later, Ayre sent me a pair of MX-Rs to audition with the KX-R. My primary source was Ayre’s C-5xe universal player; the speakers used included Wilson WATT/Puppy 8s, Avalon Indras, and Thiel CS3.7s.

Spinning on the air

Ayre claims that the KX-R benefits from break-in, and that, because each input uses a different path on the input circuit board, each requires its own break-in period. Maybe so in their Boulder listening room, but the KX-R sounded good from the go in Brooklyn. I mention this because I sometimes get queries from readers about break-in, asking how long they should “cook” a component before listening to it. My response is pretty much Play it, and count as a blessing every dollop of improvement. The KX-R started out in the front rank; if it gets even better, well, lucky Ayre customer!

I’ll start with something that sounds simple: The KX-R was really quiet. (If this were a movie, somebody would have to say, “Yeah. Too quiet.”) Aren’t all audio components these days? Well, sure, but the KX-R, with an activated input selected and set to regular listening volume, was far more silent than the tomb. As Hansen said about the air, you don’t notice it till it’s gone.Music sounded especially alive through the KX-R. I noticed this as much with the MF Nu-Vista 300 as I did with the MX-Rs. Want jump factor? The KX-R had it. John Atkinson kindly hand-delivered a CD-R containing his production mix of Cantus’s While You Are Alive (CD, Cantus CTS-1208, available by the time this sees print), and I couldn’t wait to hear it through my system with the KX-R.

Oh. My. God.

Not only is While You Are Alive the best performance I’ve ever heard from Cantus, it’s JA’s finest recording to date. From the opening notes of Eric Whitacre’s Lux Arumque, I was hearing extremely deep into the hall. The “beating” within the harmonies sounded phenomenally lifelike, and the distinctive Sauder Hall ambience surrounding Paul Nelson’s “A Lullaby” was as concrete as the singers themselves.

Then, when Edie Hill’s “A Sound Like This” began, with its urgent exhortation to “Listen!,” I just about jumped out of my skin. You’d think that triggering my fight-or-flight response would have been an unpleasant experience, but I just sat there grinning at the illusion that I was there. Then Cantus began singing harmonies that chased around the soundstage before blooming into a major chord—all interspersed with more whispered exclamations. The KX-R just kept taking me deeper and deeper into the soundstage—and my grin stretched to rival Heath Ledger’s.

But that was nothing. When I wrote Cantus’s music director, Erick Lichte, to congratulate him on the disc, he informed me that I should hear JA’s pre-production master at 24-bit/88.2kHz resolution—and said to tell JA that he’d okayed a DVD-Audio dub.

O.M.G.2

Here’s a little game you can play at home: Take everything I said above and, for the hi-rez version, add only more so—especially any part referring to the acoustics of Sauder Hall. (I’m not describing the hi-rez version only to taunt you—Erick Lichte wants to release it in the not-too-distant future. Stay tuned.)

“9/11,” from John van der Veer’s The Ark (CD, Naim CD 015), is, yes, an attempt to describe the events of 9/11/01 with five acoustic guitars. It begins with a strummed alarm, evocative of a fire station’s call-out bell, and is overwhelmed by an urgent bass continuo and several excursions into melodic fragments. It’s close-miked and, in one sense, not “realistic.” However, the sonic world the track creates is convincing and immersive. It’s also unbelievably moving, and the Ayre vividly conveyed the performance’s deep musicality.

My buddy Jeff Wong recently introduced me to the Beau Hunks, the Dutch band devoted to re-creating Leroy Shield’s scores for the Little Rascals and Laurel & Hardy comedies of the 1930s. If, like me, you grew up in an era when local TV stations repeatedly ran those old Hal Roach shorts, this music is practically ingrained in your DNA—but you’ve never heard it like this.

“Early Morning,” from On to the Show! The Beau Hunks Play More Little Rascals Music (CD, Koch Screen 3-8705-2), begins with the theme played by the violins over a wash of vintage saxophone sound, the trumpet taking the high lead—but everybody gets some time in the spotlight, even the baritone saxophonist. Thirty seconds before the end of this cue, a gong is sounded—its tone loftily floats above the group’s sound, and its overtones linger for an eternity. It was hard for me to wrap my head around all the competing images: lifelike solidity trumped by lifelike aether. The KX-R was astonishingly transparent.

Air apparent

I had on hand two preamplifiers that I consider paradigmatic—the solid-state Parasound Halo JC 2 ($4000) and the tubed Conrad-Johnson ACT2 Series 2 ($16,500)—so it seemed only natural to compare the KX-R with them. The results were simultaneously unsurprising and eyebrow raising.

On While You Are Alive (the hi-rez version, of course), the ambience of Sauder Hall was still discernible through the ACT2, but the entire soundstage seemed more compact and focused. “More focused” sounds like a good thing, right? Maybe, but the openness and sparkle of the KX-R made the ACT2’s version sound darker and, well, smaller in scale.

“9/11” was slightly less immersive through the ACT2—it seemed to lie more between the loudspeakers than all around me, as it had with the KX-R. The string harmonics seemed less zingy than through the Ayre, and to float above the fundamentals less effortlessly.

When the gong is struck in Leroy Shield’s “Early Morning,” it was less splashy through the ACT2, and not as distinct from the band’s harmonies beneath it.

Are these drastic differences? No, but they were audible—and as much as I didn’t care about them when listening to one or the other, when I compared them, I clearly preferred the KX-R.

The Halo JC 2 nailed the Sauder Hall ambience on While You Are Still Alive, but where the C-J seemed darker than the Ayre, the Parasound sounded leaner—not bleached or lightweight, just leaner. And certainly not lightweight, as it proved with those tolling tocsins on “9/11.” They came across with loads of power and leading-edge sharpness, but again the KX-R got the ratio of fundamental to harmonics more believably than did the Parasound. The JC 2 did float that gong perfectly on “Early Morning,” but it sounded a little light in the loafers on the sax choir (although the bari was very convincing).

I could live with any of these preamplifiers. In my dreams, of course—the only one I could remotely afford is the Halo JC 2, which ought to say something convincing about what Parasound hath wrought. But I digress—we are gathered today to speak of the Ayre KX-R, and I can’t think of a preamplifier that has impressed me more with its fidelity to music as I hear it.

Big air

An “extreme degree of madness” is a very fine description of how Ayre has approached the design of the KX-R. I seriously doubt that any single technology is responsible for the preamplifier’s exemplary performance. The VGT isn’t possible without an absence of feedback or the linearity that EquiLock brings to the gain transistors. Then there are the “little” touches—that extravagant display, or milling the chassis out of solid aluminum stock to create perfectly isolated pockets for each section—and so on, down to the tiniest detail. That level of fanaticism has its price. Sigh. I suspect there’s not going to be a huge amount of trickle-down with the KX-R. In Boulder, it seems, you go large or you go home.

But just as perfection has its price, it also grants, umm, perfection—or about as close to it as I’ve heard from a preamplifier to date. This irritates the heck out of me—I’ve taken it as a tenet of faith that line-level preamplifiers logically ought to have the least effect on a system’s sound of any component in the chain. I hate it when an ugly reality collides with a beautiful theory.

In my life, three much-hyped experiences have actually lived up to all the hoopla: trekking into Machu Picchu on a misty morning, climbing the Great Wall of China on a brisk December afternoon, and auditioning the Ayre KX-R. If it’s not the eighth wonder of the modern world, I say demand a recount.

Description

FEATURES:

- Variable Gain Transimpedance (VGT) volume circuit

- Ayre’s exclusive Diamond output circuit

- AyreLock power supply

- zero-feedback, fully-balanced discrete circuitry

- 60 step volume control, each of 1.0 dB

- Equilock circuitry for active gain devices

- Input ground switching for true source isolation

- Eight inputs: four balanced, four single-ended

- Two balanced outputs, two balanced tape outputs

- Dimmable silent-mode fluorescent display

- Ultra-high-speed circuit board material

- Fly-by-wire control system

- Solid aluminum monocoque chassis